See [0] for a demonstration.

I watched a documentary from the 80ies a long time ago. A mathematician (can't remember his name) who worked with von Neumann in Los Alamanos was interviewed. He described von Neumann's last weeks in the hospital - the cancer had already metastasized into his brain. The mathematician said something along this lines (I am citing from memory): "von Neumann was constantly visited by colleagues, who wanted to discuss their latest work with him. He tried to keep up, struggling, like in old times. But he couldn't. Try to imagine having one of the greatest minds maybe in the history of mankind. And then try to imagine losing this gift. I was terrible. I have never seen a man experience greater suffering."

Marina von Neumann (his daughter) later wrote this about his final weeks:

"After only a few minutes, my father made what seemed to be a very peculiar and frightening request from a man who was widely regarded as one of the greatest - if not the greatest - mathematician of the 20th century. He wanted me to give him two numbers, like 7 and 6 or 10 and 3, and ask him to tell me their sum. For as long as I can remember, I had always known that my father's major source of self-regard, what he felt to be the very essence of his being, was his incredible mental capacity. In this late stage of his illness, he must have been aware that this capacity was deteriorating rapidly, and the panic that caused was worse than any physical pain. In demanding that I test him on these elementary sums, he was seeking reassurance that at least a small fragment of this intellectual powers remained." [1]

[0] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLbllFHBQM4

[1] https://www.amazon.com/Martians-Daughter-Memoir-Marina-Whitm...

[1] https://www.amazon.com/Martians-Daughter-Memoir-Marina-Whitm...

On the European side, it was one of the greatest acts of self-sabotage seen at a civilizational scale. At the American end, it was a boon. There were more Noble prize winners hanging around coffee machines than you could shake a stick at.

The analysis fails to account for this; for e.g. they weren't intelligent just because they were of jewish heritage. They fled because they were intelligent and jewish. And those who didn't flee were killed. Is it any wonder that a list of fleeing European geniuses that the US govt. allowed entry into the States is dominated by jewish geniuses?

Out of this list, the only anomaly that truly stands out, and is perhaps the reason why the term "The Martians" was coined is John von Neumann. Quoting from a prior comment,

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=25455028

It is difficult to overstate just how smart and well rounded von Neumann was. Most contemporary accounts are from the outside looking in, but his mind was truly extraordinary. He wasn't just a genius in one capacity, but he was a genius in every capacity. It is tempting to think of him as a savant, but he was far from it. He was social, brilliant, artistic, ethically considerate, and gifted in every sense of the word. His mind is the kind of mind that comes along only once in a millennia. And it becomes more and more obvious the closer you get to him.

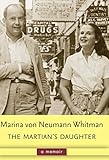

One of the best memoirs I've read is that of Marina Whitman née von Neumann, his daughter. It is her memoir, with her memories and her extraordinary life and career. But her genesis was this extraordinary being. von Neumann doted on her. He loved her and tried to fulfil the whole of her extraordinary being and train her gifted mind. The result was a woman who became an extraordinarily perceptive economist who helped guide some of the economic policy of the United States. In a way, this wasn't unexpected, as she was, of course, von Neumann's bridge to the future.

I would like to avoid reducing her story to him, but she offers a unique, familial glimpse into his mind. The early parts of her book deal with her father, and talk about his extraordinary mind. It's genuinely hard to capture the true dimensions of his mental prowess. And it's harder to capture the fact that he knew it and he tried to do his best to live up to it. That's what's so special about von Neumann. He wasn't just the greatest mind of the past millennia in sheer intellectual throughput and ability; he was a mind willing to make sacrifices to leave the Earth better than he found it. As his daughter puts it,

> Were it not for his oft-repeated conviction that everyone—man or woman—had a moral obligation to make full use of her or his intellectual capacities, I might not have pushed myself to such a level of academic achievement or set my sights on a lifelong professional commitment at a time when society made it difficult for a woman to combine a career with family obligations.

and,

> But my father's intellectual appetite was by no means narrowly confined to mathematics, and his passion for learning lasted all his life. He was multilingual at an early age; and until his final days, he could quote from memory Goethe in German, Voltaire in French, and Thucydides in Greek. His knowledge of Byzantine history, acquired entirely through recreational reading, equaled that of many academic specialists. My mother used to say, only half jokingly, that one of the reasons she divorced him was his penchant for spending hours reading one of the tomes of an enormous German encyclopedia in the bathroom. Because his banker father felt that he needed to bolster his study of mathematics with more practical training, Johnny completed a degree in chemical engineering at the Eidgennossische Technische Hochschule (ETH) in Zurich, at the same time that he received a PhD in mathematics from the University of Budapest, both at age twenty-two.

He became cynical over time. She describes his deep pessimism of humanity; something compounded by The Bomb. But then again who hasn't become a pessimist with time? He still tried to fix humans and give them things that would help move them forward. And yes, I'm talking about him separately from the rest of humanity, because his mind was profoundly different from the rest of humanity. As the article quotes Hans Bethe's famous saying, "I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann's does not indicate a species superior to that of man." He was The Martian.

I don't wish to spoil the book for those who'd like to read it, but the prologue is heart wrenching. He died far too young. I can't imagine what he might have transformed had he lived into his nineties and hundreds.

> The more important consideration, though, was national security. Given the top secret nature of my father's involvements, absolute privacy was essential when, in the early stages of his hospitalization, various top-ranking members of the military-industrial establishment sat at his bedside to pick his brain before it was too late. Vince Ford, an Air Force colonel who had been closely involved in the supersecret development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), along with General Bernard Schriever and my father, was assigned as his full-time aide. Eight airmen, all with top secret clearance, rotated around the clock. Their job was both to attend to my father's everyday needs and, in the later stages of his illness, to assure that, affected by medication or the advancing cancer, he did not inadvertently blurt out military secrets.

And this, the saddest part,

> After only a few minutes, my father made what seemed to be a very peculiar and frightening request from a man who was widely regarded as one of the greatest—if not the greatest—mathematician of the twentieth century. He wanted me to give him two numbers, like seven and six or ten and three, and ask him to tell me their sum. For as long as I could remember, I had always known that my father's major source of self-regard, what he felt to be the very essence of his being, was his incredible mental capacity. In this late stage of his illness, he must have been aware that this capacity was deteriorating rapidly, and the panic that caused was worse than any physical pain. In demanding that I test him on these elementary sums, he was seeking reassurance that at least a small fragment of his intellectual powers remained.

> I could only choke out a couple of these pairs of numbers and then, without even registering his answers, fled the room in tears. Months earlier we had talked, with a candor rare for the time, about the fact that, at a shockingly young age and in the midst of an extraordinarily productive life, he was going to die. But that was still a father-daughter discussion, with him in the dominant role. This sudden, humiliating role reversal compounded both his pain and mine. After that, my father spoke very little or not at all, although the doctors couldn't offer any physical reason for his retreat into silence. My own explanation was that the sheer horror of experiencing the deterioration of his mental powers at the age of fifty-three was too much for him to bear. Added to this pain, I feared, was my apparent betrayal of his dreams for his only child, his link to the future which was being denied to him.

Whitman, Marina. The Martian's Daughter (p. 3). University of Michigan Press. Kindle Edition.

https://www.amazon.com/Martians-Daughter-Memoir-Marina-Whitm...

On a more shameless note, I'm compiling this as a part of my Project Karl. It's one of those books that I think everyone should know about and read, but few do. https://www.projectkarl.com