I'll give an example here of how Chinese characters reflect speech more than they reflect meaning-as-such. Many more examples are possible. How you might write the conversation

"Does he know how to speak Mandarin?

"No, he doesn't."

他會說普通話嗎?

他不會。

in Modern Standard Chinese characters contrasts with how you would write

"Does he know how to speak Cantonese?

"No, he doesn't."

佢識唔識講廣東話?

佢唔識。

in the Chinese characters used to write Cantonese. As will readily appear even to readers who don't know Chinese characters, many more words than "Mandarin" and "Cantonese" differ between those sentences in Chinese characters.

[1] http://www.amazon.com/Chinese-Language-Fantasy-John-DeFranci...

[2] http://www.amazon.com/Visible-Speech-Asian-Interactions-Comp...

[3] http://www.amazon.com/Ideogram-Chinese-Characters-Disembodie...

I read quite a few books about speed-reading when I was a university student in the early 1970s, putting the techniques to the test while taking courses in linguistics, foreign languages, history of technology, and Japanese literature in English translation. There are a number of good books about how to improve reading skills, with various levels of credulity about "speed-reading" claims. After my own research and experience, I have to agree with the paragraphs in the article submitted here based on more recent research:

"Ronald Carver, author of the 1990 book The Causes of High and Low Reading Achievement, is one researcher who has done extensive testing of readers and reading speed, and thoroughly examined the various speed reading techniques and the actual improvement likely to be gained. One notable test he did pitted four groups of the fastest readers he could find against each other. The groups consisted of champion speed readers, fast college readers, successful professionals whose jobs required a lot of reading, and students who had scored highest on speed reading tests. Carver found that of his superstars, none could read faster than 600 words per minute with more than 75% retention of information.

"Keith Rayner is a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and has studied this for a long time too. In fact, one of his papers is titled 'Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research,' and he published that in 1993. Rayner has found that 95% of college level readers test between 200 and 400 words per minute, with the average right around 300. Very few people can read faster than 400 words per minute, and any gain would likely come with an unacceptable loss of comprehension."

I figure that my comfortable, steady reading speed in materials on a wide variety of subjects at an upper-division undergraduate to graduate school level is about 500 words per minute, with good comprehension. I plainly don't need "tl;dr" summaries of articles submitted to HN as often as many HN participants ask for those. (To be sure, many HN participants read English as a second language, and we should admire people who come here to participate in a second language, something very few Americans could do in a non-English-language online community.) I definitely read more slowly and with less comprehension on the first pass in Chinese or in German, my two strongest languages for second-language reading, but I have read whole books in both of those languages for fun or for research. I have diminishing ability to read other languages that are mentioned in my user profile here.

tl;dr: Don't worry about fancy eye movements too much, and don't worry about subvocalization too much. Just read steadily and think about what you are reading while you are reading it for best memory of what you read and best comprehension of what the author was trying to say. Building up your vocabulary--by more reading, of course--is the best way to build up your reading speed.

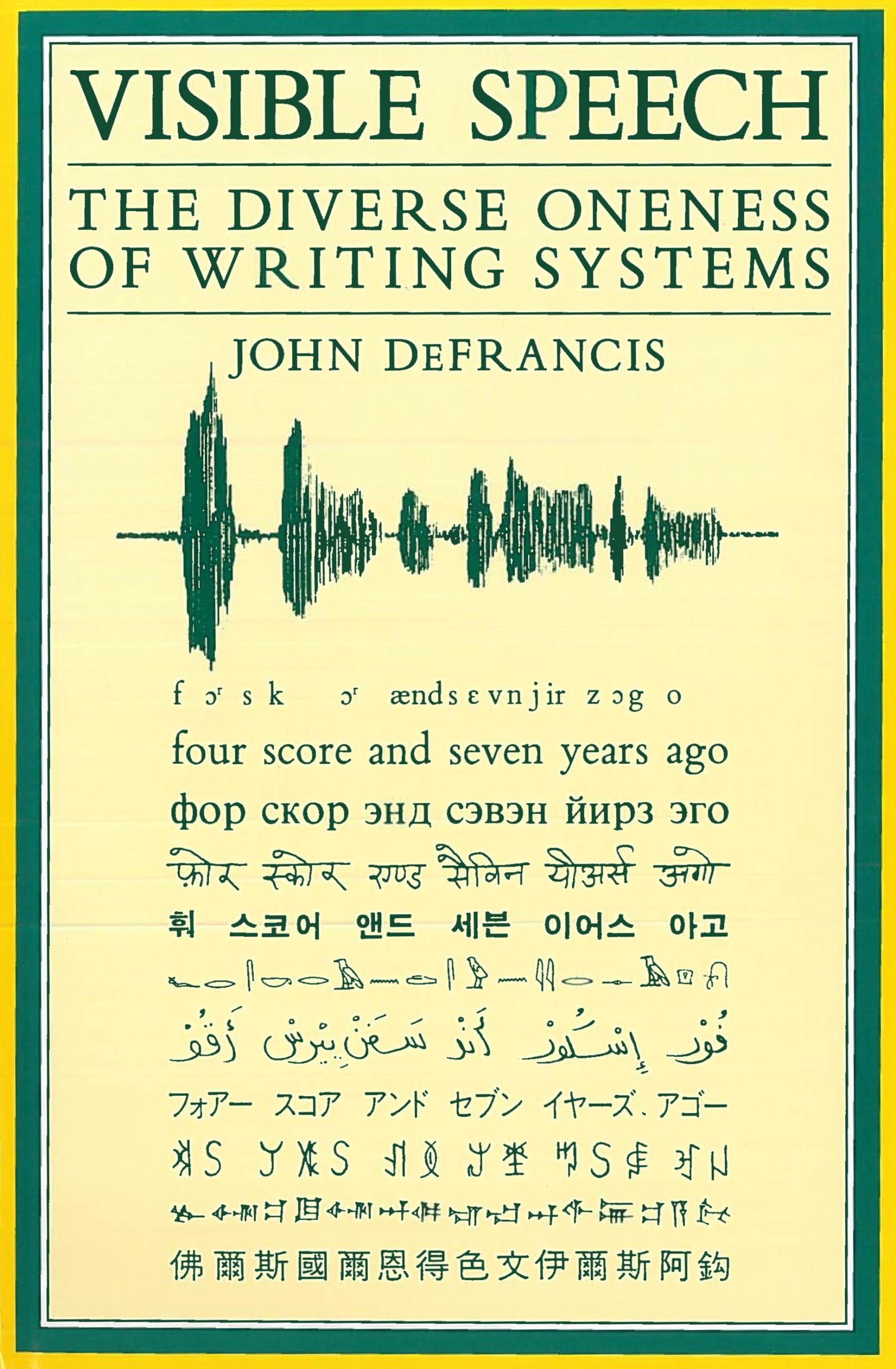

AFTER EDIT: The claim in another subthread here is specifically WRONG that Chinese constitutes any kind of proof about subvocalization. I'm not committing to a position on whether or not subvocalization, as defined by throat muscle movements, always occurs in reading, but I know from the books Visible Speech by John DeFrancis (a scholar of Chinese)

http://www.amazon.com/Visible-Speech-Asian-Interactions-Comp...

and Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention by Stanislas Dehaene (a neuroscientist who does brain imaging studies)

http://www.amazon.com/Reading-Brain-Science-Evolution-Invent...

and from my own study of four different Sinitic modern languages (Mandarin, Cantonese, Taiwanese, and Hakka) that all writing systems, properly so called, are systems for writing out speech. Writing is based on speech everywhere in the world and the Chinese writing system is full of clues that most written characters are based on the SOUND of spoken morphemes.

How you might write the conversation

"Does he know how to speak Mandarin?

"No, he doesn't."

他會說普通話嗎?

他不會。

in Modern Standard Chinese characters contrasts with how you would write

"Does he know how to speak Cantonese?

"No, he doesn't."

佢識唔識講廣東話?

佢唔識。

in the Chinese characters used to write Cantonese. As will readily appear even to readers who don't know Chinese characters, many more words than "Mandarin" and "Cantonese" differ between those sentences in Chinese characters.

How you might write the conversation

"Does he know how to speak Mandarin?

"No, he doesn't."

他會說普通話嗎?

他不會。

in Modern Standard Chinese characters contrasts with how you would write

"Does he know how to speak Cantonese?

"No, he doesn't."

佢識唔識講廣東話?

佢唔識。

in the Chinese characters used to write Cantonese. As will readily appear even to readers who don't know Chinese characters, many more words than "Mandarin" and "Cantonese" differ between those sentences in Chinese characters.

Chinese characters still represent SPEECH (not ideas or abstract concepts) and do so in a way that is specific to the particular Chinese (Sinitic) language that one speaks. The long story about this can be found in the books The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy[1] or Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems[2] by the late John DeFrancis or the book Ideogram: Chinese Characters and the Myth of Disembodied Meaning[3] by J. Marshall Unger. The book Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention[4] by Stanislas Dehaene is a very good book about reading in general, and has a good cross-cultural perspective.

Many other examples of words, phrases, and whole sentences that are essentially unreadable to persons who have learned only Modern Standard Chinese can be found in texts produced in Chinese characters by speakers of other Sinitic languages ("Chinese dialects"). Similar considerations apply to Japanese, which is not even a language cognate with Chinese, and also links Chinese characters to particular speech morphemes (whether etymologically Japanese or Sino-Japanese) rather than with abstract concepts.

[1] http://www.amazon.com/Chinese-Language-Fantasy-John-DeFranci...

[2] http://www.amazon.com/Visible-Speech-Asian-Interactions-Comp...

[3] http://www.amazon.com/Ideogram-Chinese-Characters-Disembodie...

[4] http://readinginthebrain.pagesperso-orange.fr/intro.htm